What is Zooarchaeology?

Zooarchaeology is a hybrid discipline that combines zoology (the study of animals) and archaeology (the study of past human culture). Zooarchaeologists, also called archaeozoologists and faunal analysts, study animal remains from archaeological sites. These remains include bones, teeth, scales, mollusk shells, egg shells, horn, antler, chitin from insects and crustaceans, and sometimes hair, skin, and mummies. Zooarchaeologists study how people used and interacted with animals in the past. Animal remains provide clues about what the natural environment was like and how it changed through time. They also provide clues to human cultural practices. Zooarchaeologists contribute to studies of human technology, diet, economy, and animal domestication, as well as trade or exchange, dress and ornamentation, social status and interactions, and religious beliefs.

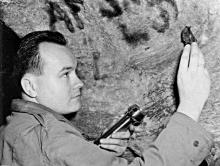

Dr. Paul Parmalee of the Illinois State Museum is one of the founders of this type of research. In the 1950s he studied animal remains from Modoc Rock Shelter in Randolph County, Illinois. He developed one of the best comparative skeletal and mollusk collections in the Midwestern United States to help him identify bones and shells from Modoc and other sites. Zooarchaeologists from across the country come to the Illinois State Museum to use this important comparative collection for their research.

This map shows our study area in the interior part of the eastern United States and the locations of the archaeological sites that we included for our grant project. The subregions we studied include the Great Lakes area of Michigan (pink), Prairie Peninsula of Illinois and Missouri (brown), Ohio River Drainage of Indiana, Illinois, and Kentucky (blue), and the Mid-South of Tennessee and Alabama (yellow).

This website illustrates what we can learn from faunal remains from archaeological sites. It demonstrates the value of animal remains for answering questions about environments, human use of animals, and broader cultural issues during the Archaic Period (10,500-2,500 radiocarbon years before the present) in the interior part of eastern North America. It is based on research funded by a grant from the National Science Foundation (BCS-1430754).

We primarily use examples from two important Illinois archaeological sites that were studied as a part of this grant. These sites are the Koster site, located in the lower Illinois River valley in Greene County, and Modoc Rock Shelter, located in the middle Mississippi River valley in Randolph County (see map). Both sites have occupations that span the Archaic Period of American Indian history. To learn more about the Archaic Period, please visit the Illinois State Museum web module on the Archaic Period in the MuseumLink Native American website https://www.museum.state.il.us/muslink/nat_amer/pre/htmls/archaic.html

Our research for this grant demonstrates the importance of preserving information about faunal remains in electronic databases and sharing these databases with other researchers. For more information on this research project and our research team, please visit the About section.

Archaeologists recovered extremely large quantities of animal remains (bones and shells) from the Koster site in Greene County, Illinois. Why are there so many animal remains at archaeological sites such as Koster? Image used with permission of Center for American Archeology.

Why are there animal bones at archaeological sites?

Many zooarchaeologists examine how animals went from the land of the living to remains at an archaeological site. This area of research is called taphonomy. It includes how the remains ended up at the site, became buried, and how they were modified and preserved.

For our grant we looked at evidence for destruction of bone by weathering, chewing and gnawing, butchering, fragmentation, and heavy burning. We also analyzed whether the density of bones affected the numbers of bones preserved. For example, were more high density bones preserved than low density bones. Loss of low density bones could bias our interpretations. We try to figure out whether the bones are present because of natural causes and/or because of human activities. We also examine natural and cultural actions that contribute to the destruction or preservation of bone.

This type of research helps us understand differences in the condition and preservation of remains for different kinds of animals such as mammals and birds and for different types of bones. These differences might cause us to misinterpret the amount of different kinds of animals that were present. It helps us make more meaningful comparisons of faunal remains within and among sites.

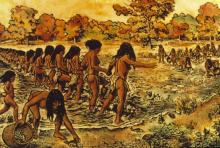

This artistic representation of life in one of the Archaic Period base camps at the Koster site by George Armstrong provides some clues why we find so many bones at the site. Image used with permission of the Center for American Archeology.

Human Activities

The animal remains excavated at most archaeological sites, including the Koster site and Modoc Rock Shelter, are primarily from animals that were hunted or collected by people. Ancient hunters, trappers, and fisherman brought animals back to their camps for food, raw materials, and other purposes. They may have eaten some of the animals or left parts of animals at the location where they were killed or collected.

At many archaeological sites, most of the bones and shells at camps are leftovers from meals. People at camps often broke bones into smaller pieces during butchering and food preparation. They may have cut up the carcasses of larger animals such as white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) and shared parts with other families at the camp. They may have steamed, boiled, or roasted parts of animals. Even though meat surrounded the bones, cooking may have stained and weakened them.

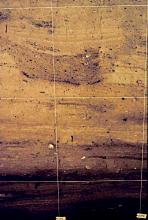

This image of the profile of the wall of the 1966 and 1980 excavations at Modoc Rock Shelter shows a basin-shaped pit feature (top part of image) and flat, sheet midden deposits (lower part of image).

After people ate the edible parts of animals, they threw away the inedible parts. They may have thrown the bones into piles, pits, and relatively flat layers of garbage called sheet middens. The image of the profile of the 1956 and 1980 excavation wall at Modoc Rock Shelter (to the left) shows feature and midden deposits. The strings on the profile wall of the Modoc excavation mark a one meter grid. The complete one meter square on the top right of the image intersects the profile of a pit that was dug by Archaic Period people. The pit extends to both sides of the string that runs down the center of the image. You can see the outline of the bottom and sides of the pit, the dark-colored organic pit fill, and a layer of charcoal along its base. The one meter squares below the pit show flat, sheet midden deposits of refuse from human activities. The abundant charcoal in the deepest layers contributes to their dark color.

Sometimes people disposed of bones outside their camp such as in a nearby gully. Sometimes they threw the bones in the fire to dispose of garbage or perhaps out of respect for the animals they consumed. As we will discuss later, sometimes people piled or buried bones in in special contexts.

The people living at a camp likely trampled any bones that were laying on the ground surface. Bones thrown into pits were likely better protected from trampling. Human activities such as these left marks and damaged and destroyed bone and shell. At the Koster and Modoc sites, most of the faunal remains came from middens, but some came from features such as hearths and various kinds of pits. We are comparing the preservation and differences in kinds of animals recovered in these different kinds of contexts.

Archaic Period people at the Koster site shaped these animal bones into decorative pins. Animal bones and shell provided important raw materials for tools and ornaments. Image used with permission of Center for American Archeology.

Bones and shells do not just represent food refuse. People made some bones and shells into tools and cared for them so they could be reused. Some of these items may have been used in special ceremonies and buried in special contexts. Furs, skins, feathers, bones, and shells were made into clothing and ornaments, but only the durable parts such as bone and shell normally survived.

Many cultural practices incorporated animals. They were not just sources of food and raw material. People had special relationships with some animals, and some may have been important to their beliefs and religious practices. Some animals such as dogs or parts of animals made into objects, such as fans made from bird wings, were sometimes intentionally buried. Such special contexts suggest special relationships. Intentional burial of animals and artifacts made from animal remains also made them less subject to destruction.

Dr. Parmalee observed this live bat in an Illinois cave. Bats live and hibernate in caves and rock shelters. When they die, their bones may be incorporated in the sediments.

Natural Occurrences and Natural Forces

Sometimes the animal remains at archaeological sites were not associated with the past human activities. For example, burrowing animals may have died at the site—sometimes long after the people had left. Small animals such as rodents, snakes, frogs, and toads may have fallen into open pits and become trapped. Caves and rock shelters may contain the bones of other animals that lived and/or died at the site such as bats and carnivores. We have seen live bats at Modoc Rock Shelter, and some bat bones are present in the archaeological deposits at the Shelter. The conditions of these remains and their more complete skeletons sometimes help archaeologists recognize these natural occurrences.

This profile of the excavation at the Koster site shows the layering of Archaic Period camps with the older camps at the bottom. Natural deposition of sediments occurred rapidly throughout most of the Archaic Period. Rapid burial in alkaline (non-acidic) sediments contributed to excellent preservation of bone and shell at both Koster and Modoc Rock Shelter. Image used with permission of Center for American Archeology.

Natural agents also leave marks on and destroy bones. Domestic dogs living with the people at Archaic Period camps sometimes chewed or ate bones, especially those from food refuse. Domestic dogs were present during the Archaic Period occupations at both Koster and Modoc Rock Shelter, and we find animal bones that have been chewed by carnivores—likely the dogs. Rodents sometimes gnawed bones and antler. We find rodent bones and rodent-gnawed bones in the Archaic camps at Koster and Modoc. The proportions of carnivore and rodent gnawed bones at Modoc and Koster are low.

Camps at the Koster site and Modoc Rock Shelter were situated along the base of bluffs in locations where bones were rapidly buried. The sediments that eroded from the bluff tops and washed in from nearby creeks were non-acidic. Sediments built up rapidly at these sites and left layers of camp site remains with the oldest on the bottom and the youngest on the top. Bones at these sites are well preserved.

Some Archaic camps in Illinois were situated in areas where sediments were not being rapidly deposited, such as in the uplands. Bones were less likely to be preserved at these camps. Bones left on the ground surface were exposed to the natural elements ─ rain, snow, freezing and thawing, wind, and sun. These natural forces hastened the weathering and decay of animal remains. Some camps in Illinois occurred in areas with acidic soils such as pine forests or in areas that were alternately wet and dry such as low-lying floodplains. Bones were not well preserved in these conditions. Only the durable stone artifacts are preserved at sites in these areas.

Archaeologists primarily dry-screened sediments from the Koster site through 1/2" mesh screens to collect faunal remains and artifacts. They used a small board to push sediments through the screen. Image used with permission of Center for American Archeology.

Recovery of Bones

Archaeologists recover animal bones as they are excavating. Bones and other remains may be hand-collected while digging, sieving sediments through screens, or recovered through water flotation of sediments. The way the archaeologist collects the bones has big impacts on the size of animals and types of bones that will be represented. Use of a fine mesh screen (usually 1/16" mesh) results in better recovery of remains from small animals and small bones from other animals.

Zooarchaeologists pay special attention to the size of the mesh used to recover animal remains. Hand collection and screening of sediment through 1/4" or 1/2" mesh screen recovers larger bones and bones from larger animals. To recover small-scale remains including small bones and bones from smaller animals, many archaeologists collect standard-sized sediment samples for processing through a smaller mesh screen often using water flotation.

Archaeologists at the Koster site, processed flotation samples with wash tubs in the Illinois River. Image used with permission of Center for American Archeology.

At the Koster site, excavators individually plotted bones on maps and hand-collected them for some deposits. For other deposits at Koster, they dry screened sediments through 1/2" mesh. To collect small-scale remains, they saved bushel baskets of screened sediment from each excavation level for water flotation. They processed flotation samples in wash tubs fitted with a 1/16" mesh screen bottom. During flotation, sediments pass through the 1/16" mesh screen, and animal remains and other heavy remains collect on the screen. We call this processed sample the heavy fraction. For this type of flotation, archaeologists use a scoop fitted with 1/32" mesh to scoop out the light remains that float such as plant remains, small gastropod (snail) shells, and fish scales. We call this processed sample the light fraction.

Archaeologists processed sediments from the 1980 Modoc Rock Shelter excavations by running pressurized water through nested 1/4" and 1/16" screens. This technique is called water screening.

During the 1950s excavations at Modoc Rock Shelter, archaeologists dry screened sediments through 1/4" mesh. Archaeologists working at Modoc in 1980 water-screened sediments through nested 1/4" and 1/16" mesh screens. During the 1984 and 1987 seasons at Modoc Rock Shelter, excavators dry screened sediments through 1/4" mesh.

Archaeologists at Modoc Rock Shelter processed sediment samples collected for flotation using a flotation barrel designed by archaeologist Patty Jo Watson.

During the 1950s excavations at Modoc Rock Shelter, the smallest mesh size used was 1/4". During 1980 excavations at Modoc Rock Shelter, archaeologists collected standard-sized buckets of sediment from each excavation level for water flotation using 1/16" mesh, and as noted above also water-screened all other sediments through 1/16" mesh. They used a flotation barrel for the flotation process. For this type of flotation, running water connected to the barrel washes the sediment to the barrel's bottom. Heavy, small-scale remains such as bones and freshwater mussel shells are collected in a 1/16" mesh screen in the barrel. Light remains that float (mostly plant remains, small gastropod shells, and fish scales) flow through a shoot and are collected in a 1/32" mesh screen. As noted above, the processed samples are called the heavy and light fractions. Archaeologists used the same flotation process for the 1984 and 1987 excavations at Modoc Rock Shelter. Use of flotation greatly improved the recovery of small bones and remains of bones from small-bodied animals including rodents and fish.

We sometimes refer to the remains collected on the large-mesh screens as macrofauna and the remains collected on fine-mesh screens as microfauna. How would the use of a large-mesh screen, such as a 1/2" mesh screen, affect the kinds of faunal remains recovered at the Koster site? Which screen mesh size do you think would recover the most bones from small-bodied fish and rodents? Research for our grant shows that there are strong differences between the kinds of animals represented in the samples processed through 1/4" or 1/2" mesh and 1/16" mesh at a site. If there are great differences in the kinds and body sizes of species recovered through large-mesh screening and flotation, then it is extremely important to study and present the results for both types of samples.

Zooarchaeologists make decisions about what to analyze. They rarely analyze all of the faunal remains from a site because analysis of bones is time consuming. When comparing animal remains from different camps at a site or among different sites, it is important to consider what was excavated at the site and how it was recovered. It is also important to consider how much and what kinds of samples were analyzed by the zooarchaeologist to see if the faunal assemblages from different occupations at a site or for different sites are comparable.

Why are zooarchaeological data important?

The section below outlines some of the many ways that zooarchaeological data contributes to the understanding of the natural and cultural worlds. Our research informs a wide variety of researchers today and will do so in the future. Our data also satisfies natural human curiosity about what life was like in the past.

History before Writing

If we make a very conservative estimate that humans entered North America about 14,000 years ago, then the 8,000 year-long Archaic Period covers more than half of that time. In fact, most of human history in North America predates the written record. Father Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet left the first written descriptions for the Illinois area in 1672. If history has value, then history before the written record clearly has value as well and represents many more years of the human experience. For the distant past, archaeology provides a primary means for exploring history. As we will demonstrate in this module, the study of animal remains from archeological sites provides rich records for understanding past environments and human cultural practices.

Understanding Past Environments

Animal remains from archaeological sites provide clues to the natural environment during the time the site was occupied. They show us how humans were interacting with the natural environment in their daily lives. Understanding environments and environmental change over thousands of years is of interest to a wide variety of researchers including archaeologists, historians, geologists, paleontologists, zoologists, botanists, paleoecologists, climatologists and climate modelers, and wildlife and land managers.

Our Archaic Period data provide a record of environments from 10,500 to 2,500 radiocarbon years before the present. This period predates evidence for extensive human modifications of the landscape. Some scientists refer to these data as baseline data that illustrate natural conditions prior to major human modifications and impacts on the environment. The Archaic Period falls within the current geologic period, called the Holocene. Some scientists argue that a new geological epoch, should be named to recognize the period when people began having major impacts on the environment. They advocate calling the new epoch the Anthropocene and argue over when it started. Although we think Archaic Period people had local impacts on plant and animal communities through hunting and collecting and burning and by the latter part of the period by cultivating plants. Our data suggest that humans are not dominant causes of environmental change during the Archaic Period.

Studies of animal remains from the Koster site in the lower Illinois River valley enriched this George Armstrong illustration of life at base camp about 6,000 years ago. Used with permission of the Center for American Archeology.

Human Interactions with Animals and Cultural Practices

Humans have always interacted with animals. Animal remains from archaeological sites provide a record of human use of animals for food, raw materials for tools, clothing and ornaments, and special uses that relay information on social interactions and religious practices. They provide evidence for attempts to manage animal populations and habitats and also for the development of animal domestication. They tell us about human cultural practices such as hunting, fishing, cooking, technology, clothing and ornamentation, social interactions, religious practices, and much more. They help fill in the story of human lifeways for the long expanse of time prior to the written record.

Archaic Period people may have intensively harvested the fish in floodbasin lakes by 6,000 years ago as shown in this George Armstrong illustration. As noted in this section, Archaic Period people had local impacts on animal populations. Used with permission of the Center for American Archeology.

Human Impacts on Animal Populations

Humans have impacts on animal populations. They kill animals for food and raw materials. Some people keep live animals. For example, we know that Archaic Period people kept domestic dogs. Human use of animals has the potential to affect the sizes and distributions of wild animal populations. We can look for these impacts in the archaeological record. During the Archaic Period, Archaic Period people may have had local impacts on animal populations. For example, they intensely harvested fish from small floodbasin lakes in the lower Illinois River valley. However, annual spring and fall floods of the Illinois River would have naturally restocked lakes.

Importance for Conservation and Restoration Projects

When wildlife and land managers restore landscapes and reintroduce animals to environments, they research what kinds of animals lived there in the past. Information on animal species from historic records and archaeological sites helps biologists know which species to reintroduce to aquatic and terrestrial habitats. Remains from archaeological sites provide baseline data on the kinds of species and their distributions prior to extensive human modification of rivers and the land. They help wildlife and landscape managers know what kinds of animals lived and thrived in similar habitats in the past. These data help them make decisions about whether a species should be introduced for a restoration or management project.

The Neotoma Paleoecology Database includes data based on animal remains from archaeological sites, including Koster and Modoc Rock Shelter. In fact, archaeological faunal data consitute a large part of the database. This database, funded by the National Science Foundation, documents long-term changes in climate and environment. It is used to test climate models that predict future climate change.

Human and Animal Responses to Climate and Environmental Change

Animal bones at archaeological sites provide evidence for climate and environmental changes. During the long Archaic Period, animal and human populations responded to climate changes, including rapid change at the end of the most recent Ice Age and a long period of warming and drying during the Holocene. We examine evidence for animal responses to the natural changes in climate, landforms, rivers, and plant and animal communities. We explore human responses to changes in the same natural features including the abundance and distribution of animals.

Scientists use the faunal data from archaeological sites to study long-term climate and environmental change. They use the past to model and predict how plants and animals will respond to future climate changes. The Neotoma Paleoecology Database includes data for plants and animals based on remains from paleontological and archaeological sites and natural settings such as lakes and bogs. It includes data from the original FAUNMAP database and North American Pollen Database that were developed at the Illinois State Museum and funded by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the National Science Foundation.

Paleoecologists and climate modelers use data from Neotoma to study changes in the distribution of plants and animals over the last two million years. Climate modelers have used these data to test their contemporary climate models that they use to predict future climate change and impacts. They use the contemporary climate model to "postdict" the conditions and plant and animal responses during past periods of known environmental change such as the end of the most recent Ice Age. They then test what the model yields for the past by comparing to what actually happened based on the Neotoma database.

Organization of Website

This website introduces the general public to the science of zooarchaeology and what we have learned from the bones and shells from archaeological sites. The examples provided stem from the research undertaken for the NSF grant with a focus on interpretations from the Koster site and Modoc Rock Shelter in Illinois. The website is designed for the general public and to be accessible to students from seventh grade through undergraduate college.

Zooarchaeology

The section that you hopefully just completed introduces the science of zooarchaeology, how animal remains become incorporated in archaeological sites through natural and cultural processes, how archaeologists recover animal remains, and why zooarchaeological data are important.

Clues from Bones

We review the clues that animal remains from archaeological sites provide about animals, including species represented, types and parts of bones and shells recovered, natural and human modifications to the remains, and characteristics of animals such as their size and age. We also discuss how we count numbers of bones and individual animals and how we record and share all of this information in databases.

Past Environments

We explore how animal remains reveal information about past environments and climate. We provide information on the ages of the Archaic Period sites studied for our research project and an overview of major environmental changes following the most recent Ice Age and during the Archaic Period. We explore what our faunal datasets reveal about changes in terrestrial and aquatic environments during 8,000 year-long span of the Archaic Period. We illustrate two schemes for categorizing faunal remains into resource types and what they show us about variability in resource use and change through time during the Archaic Period.

Human Use of Animals

We explore the various ways that humans interacted with and used animals during the Archaic Period. We examine hunting and collecting and hunting techniques; evidence for management and domestication of animals; use of animals for food and raw materials for tools, clothing, and ornaments; and special use of animals or parts of animals for social and religious purposes. We examine some of the variability across our study area and change through time. We illustrate the ways that interactions with animals influenced where people chose to live and other cultural practices. We demonstrate that understanding human use of animals provides clues to important cultural issues, such as diet and health, size and location of settlements, how often people move their settlements, economy, technology, exchange, socio-political organization and interactions, and religion.

About the Project

In the final section, we review the major goals of our grant project and the importance of sharing our databases. We present our study area and the sites studied for our research. We introduce our project team and thank our sponsors and advisors.

We hope that you will explore this site in a logical order, and most of all we hope that you will enjoy learning about zooarchaeology and Archaic Period environments and lifeways.

References

Zooarchaeology

*=non-technical

*Chaplin, Raymond E. 1971. The Study of Animal Bones from Archaeological Sites. Seminar Press, New York.

Colanino, Carol E, John H. Chick, Terrance J. Martin, Autumn M. Painter, Kelly B. Brown, Curtis T. Dopson, Ariana O. Enzerink, Stephanie R. Goesmann, Tom Higgins, Nigel Q. Knutzen, Erin N. Laute, Paula M. Long, Page L. Ottenfield, Abigail T. Uehling, and Lillian L. Ward. 2017. Examination of Effects Consistent with the Anthropocene in the Lower Illinois River Valley. Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology 42(3):266-290.

Emery, Kitty F. 2003. Enduring Foundations to a Holistic Science: Lessons in Environmental Archaeology from Elizabeth S. Wing. Pp. 3-10 in Zooarchaeology: Papers to Honor Elizabeth Wing, edited by F. W. King and C. M. Porter. Florida Museum of Natural History, Bulletin, 44(1).

Fowler, Melvin L. and Paul W. Parmalee. 1959. Ecological Interpretations of Data on Archaeological sites: the Modoc Rock Shelter. Transactions of the Illinois State Academy of Science 52(3-4):109-119.

Grayson, Donald K. 1984. Quantitative Zooarchaeology: Topics in the Analysis of Archaeological Faunas. Academic Press, New York.

Limp, W. F. 1974. Water Separation and Flotation Process. Journal of Field Archaeology 1:337-342.

Lyman, R. Lee. 1994. Vertebrate Taphonomy. Cambridge Manuals in Archaeology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Lyman, R. Lee. 2008. Quantitative Paleozoology, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Morris, JoAnn and R. Bruce McMillan. 1991. Bibliography of Paul W. Parmalee. Pp. 15-21 in Beamers, Bobwhites, and Blue-points: Tributes to the Career of Paul W. Parmalee, edited by J. R. Purdue, W. E. Klippel, and B. W. Styles (editors). Illinois State Museum Scientific Papers 23, and the University of Tennessee, Department of Anthropology Report of Investigations 52.

Parmalee, Paul W. 1959. Animal Remains from the Modoc Rock Shelter Site, Randolph County, Illinois. Pp. 61-65, Appendix II, in Summary Report of Modoc Rock Shelter 1952, 1953, 1995, 1956, by Melvin L. Fowler. Illinois State Museum Reports of Investigations 8.

Parmalee, P. W., W. E. Klippel, and A. E. Bogan. 1980. Notes on the Prehistoric and Present Status of the Naiad Fauna of the Middle Cumberland River, Smith County, Tennessee. Nautilus 04(3):93-105.

Peres, Tanya M. (editor). 2014. Trend and Traditions in Southeastern Zooarchaeology. University Press of Florida, Gainesville.

Purdue, James R., Walter E. Klippel, and Bonnie W. Styles (editors). 1991. Beamers, Bobwhites, and Blue-points: Tributes to the Career of Paul W. Parmalee. Illinois State Museum Scientific Papers 23, and the University of Tennessee, Department of Anthropology Report of Investigations 52.

Read, C. E., 1971, Animal Bones and Human Behavior: Approaches to Faunal Analysis in Archaeology. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles.

Reitz, Elizabeth and Elizabeth S. Wing. 2008. Zooarchaeology, 2nd edition, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Russell, Nerissa. 2012. Social Zooarchaeology: Humans and Animals in Prehistory. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Struever, Stuart, 1968, Flotation Techniques for the Recovery of Small-Scale Archeological Remains, American Antiquity 33(3):353-362.

Watson, Patty Jo. 1976. In Pursuit of Prehistoric Subsistence: A Comparative Account of Some Contemporary Flotation Techniques. Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology 1(1):77-100.

Wing, Elizabeth. 1976. The Role of Zoology in Archaeological Research. Southeastern Archaeological Conference Bulletin 19:18-23.

Wing, Elizabeth. 2001. Potential of Zooarchaeology for Better Understanding of the Human Past. Pp. 11-19 in Ethnobiology at the Millennium, edited by R. I. Ford, University of Michigan Museum of Anthropology, Anthropological Papers, No. 91.