Even in the distant past, humans contributed to environmental change. There are numerous historic acounts of American Indians burning prairie areas to drive animals during hunting. Some archaeologists argue that such practices may have a long history. Image taken from Illinois State Museum Changes exhibition.

Environmental Indicators

Methods

The natural environment continually changes. The natural landscape includes landforms, waterbodies, and plant and animal communities. The landscape changes through time as climate and environmental systems change. Natural environments also vary across space. Climate changes may impact different regions in different ways.

Humans and other animals also change natural environments. For example, burning of prairies by humans kills trees and helps maintain the prairie. Human burning of prairies for hunting drives may have a long history. We look for evidence of human activities that would have contributed to environmental change. For example, we look for evidence for land clearing, modification of streams, management and domestication of plants and animals, and siltation and pollution caused by human activities.

It is important to understand past environments and how they changed through time. Although climate and environment limit which animals are available, they do not determine which animals people choose to use. We will explore the role of choice in the Human Use of Animals section.

The pondhorn (Uniomerus tetralasmus) freshwater mussel lives in standing water in ponds, creeks, and headwaters of streams in mud and sand bottoms. This information comes from the Illinois State Museum's website online resource on the "Fresh Water Mussel Collection." Check out this website to learn more about freshwater mussels (www.museum.state.il.us/ismdepts/zoology/mussels/index.html). Photograph taken by Karen Little.

The kinds of animals recovered at an archaeological site provide important clues about the natural environment of the area at the time when the people were living there. Some animals have specific habitat requirements. For example, some rodents only live in grasslands and some freshwater mussels, such as the pondhorn (Uniomerus tetralasmus), live in quietwater in ponds, creeks, and headwaters of streams. Species with tight requirements provide the best clues to what the environment was like in the site area. Some species can live just about anywhere. We call them cosmopolitan. They are of little value to environmental reconstructions.

We analyze the habitat preferences for all of the animals recovered at archaeological sites to understand the natural environment. We calculate the percentages of different species associated with a particular habitat to get a sense of the natural environment at the time a settlement was occupied. Sometimes the characteristics of animal species such as animal morphology and adult body size provide clues to past environments.

Some zooarchaeologists study the isotopes (different forms) of elements preserved in bones and shells to learn about characteristics of the environments occupied by the animals. We look for evidence of changes in environments through time. We also examine multiple lines of other evidence to see if they support our interpretations. For example, we look at the plant remains from archaeological sites and fossil pollen preserved in lake sediments. We also look at evidence for changes in landforms and plant communities in the region.

| Cultural Period | Cultural Subperiod | RCYBP | Geologic Period |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paleoindian | ?-10,500 | Late Pleistocene | |

| Early Archaic | early Early Archaic (EA1) | 10,500-8,700 | Early Holocene |

| late Early Archaic (EA2) | 8,700-8,100 | ||

| Middle Archaic | early Middle Archaic (MA1) | 8,100-7,400 | Middle Holocene |

| middle Middle Archaic (MA2) | 7,400-6,100 | ||

| late Middle Archaic (MA3) | 6,100-4,700 | ||

| Late Archaic | early Late Archaic (LA1) | 4,700-3,700 | Late Holocene |

| late Late Archaic (LA2) | 3,700-2,500 |

Environmental Change during the Archaic Period

The kinds and percentages of animals present at Archaic Period sites changed through time. Some of these changes are related to changes in climate and the natural environment. For example, changes in forests and rivers altered the kinds and abundance of animals that were present at different times during the Archaic Period.

For our study, we divided the Archaic Period into the Early Archaic (10,500-8,100 radiocarbon years before present), Middle Archaic (8,100-4,700 radiocarbon years before present), and Late Archaic (4,700-2,500 radiocarbon years before present). The ages of these periods are based on radiocarbon dating of organic remains such as nutshells from sites. When scientists refer to radiocarbon years before the present (RCYBP), 1950 represents the present.

We also divide these three major time periods into smaller time slices because some changes in environments and culture occurred within these major periods. The Early Archaic is divided into early and late subperiods. The Middle Archaic is divided into early, middle, and late subperiods. The Late Archaic is divided into early and late subperiods (see table to left).

The whole Archaic Period falls within the Holocene—the geologic period that follows the Pleistocene or Ice Ages. During the Pleistocene, cold glacial periods were interspersed with warmer interglacial periods. Some geologists consider the Holocene to be a warm interglacial period. The Holocene is divided into early, middle and late subperiods based on changes in climate. The Early Holocene of the Illinois area was cooler and wetter than today. The Middle Holocene was warmer and drier than today, and the Late Holocene was roughly similar to today.

This painting by Robert E. Larson depicts American mastodons (Mammut americanum) in a Late Pleistocene environment in the Midwestern United States. Spruce trees and tundra were present in the Illinois area during this cold interval.

Terrestrial Environments

The Late Pleistocene (Ice Age) environments greatly differed from those of the Archaic Period. Spruce forest and tundra were present in the Illinois area. The Paleoindians of the late Ice Age shared their environment with megafauna (very large animals) such as mammoths (Mammuthus primigenius) and mastodons (Mammut americanum). These large animals went extinct at the end of the Ice Age. Many cold-adapted species migrated north when climate rapidly warmed at the end of the Ice Age. The Ice Age environment also supported a host of smaller-bodied animals. Many of these smaller animals such as white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) and woodchuck (Marmota monax) survived the rapid warming at the end of the Pleistocene and adapted to the Holocene landscapes.

Holocene warming occurred earlier to the west and south of the Illinois area. Archaeologists recovered bison (Bison bison) bones in Early Archaic deposits at the Rodgers Shelter site in the southern Ozark Highlands of Missouri. Middle Holocene drying also occurred earlier. Archaeologists discovered bones from animal species that are restricted to western grasslands, such as pronghorn antelope (Antilocapra americana), in early Middle Holocene deposits at Rodgers Shelter. Images taken from Wikimedia Commons.

Based on archaeological and paleontological sites, the kinds of terrestrial animals available to Archaic Period peoples were mostly those we see today. However, humans eliminated some animals that were present in the Illinois area during the Archaic Period. These animals include bison (Bison bison), elk (Cervus elaphus), and black bear (Ursus americanus). However, these animals continued to occur in the wild in surrounding regions. Biologists refer to this as extirpation. Wildlife managers have reintroduced these animals to the state, but their distributions are limited and controlled.

Some animal species recovered at Archaic Period archaeological sites appear to be far outside of their historic and modern distributions. However, we have to remember that climate and environments have changed through time. At Rodgers Shelter in the southern Ozark Highlands of Missouri, archaeologists recovered remains from prairie animals. These animals include bison, spotted skunk (Spilogale putorius) and Plains pocket gopher (Geomys bursarius) recovered in the Early Archaic deposits (8,600-8,100 RCYBP). Early Middle Holocene deposits included species associated with western grasslands such as pronghorn antelope (Antilocapra americana) and Plains pocket mouse (Perognathus flavescens). These animals do not live in wild in this part of Missouri today. However climate during the Early Archaic and early Middle Archaic (8,100-7,500 RCYBP) differed from that in Missouri today. It was warmer and drier then and prairie had expanded into the area around Rodgers Shelter during this period. The expansion of prairie into the area, allowed the prairie animals listed above to live there. This prairie expansion occurred earlier in western Missouri and later in the Illinois area to the east.

Bones from tree squirrels, especially gray squirrels (Sciurus caronlinensis), are surprisingly abundant at Early Archaic sites such as Koster and Modoc Rock Shelter. Gray squirrels (upper image) are well adapted to dense forest settings. Bones from white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) are also common in Early Archaic sites, but the percentage of deer bones is often greater in Middle Archaic sites. White-tailed deer (lower image) are well adapted to open forest and forest edge where they feed on leaves and small branches of shrubs and trees. Images taken from Wikimedia Commons.

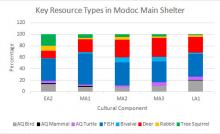

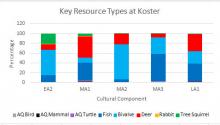

Changes in the percentages of species present at Modoc Rock Shelter and the Koster site in Illinois provide evidence for changing natural environments during the Archaic Period. During the Early Archaic, the prairie had not yet expanded in the Illinois area. The Koster and Modoc Rock Shelter sites include a few prairie taxa, such as Greater Prairie Chicken (Tympanuchus cupido), in the Early Archaic. However, none of the prairie species are historically restricted to western grasslands.

Most of the terrestrial animals found at Early Archaic sites in Illinois are associated with forest and stream-side habitats. White-tailed deer are common among the identified remains, but not as abundant as at Middle Archaic camps. Tree squirrels, especially gray squirrels (Sciurus carolinensis), are often more abundant in Early Archaic camps than in later time periods. Gray squirrels thrive in closed forest settings, which supports interpretations for a more closed forest during this time. Studies of Early Holocene landforms and fossil pollen show that climate had warmed after the Ice Age, but was cooler and wetter than today.

The forest was wetter and more closed during the Early Holocene. Because the forest canopy was closed, less sunlight reached the forest floor. Image taken from Tri-county Regional Planning Commission, Forest Management Report.

During the Early Holocene, deciduous trees, including oak, elm, and ash dominated a closed canopy forest. More of Illinois was forested than today, and there were only small patches of prairie. As noted above, the large expanse of prairie that historically covered the central part of the state had not yet expanded in Illinois. The abundance of gray squirrels in Early Archaic sites has been noted from southern Wisconsin to Northeastern Alabama. We think that the cooler, wetter Early Holocene climate and more closed forests may have been suitable for tree squirrels and detrimental for deer populations when compared to later time periods. There was less brush for browsing animals such as white-tailed deer to eat in the closed forest.

During the Middle Holocene, the forest became drier and more open. The open canopy of the forest allowed more light to reach the forest floor and increased the amount of ground cover and brushy plants. Image taken from Illinois Department of Natural Resources, Forest and Woodland, Illinois Wildlife Action Plan.

Geological research and studies of fossil pollen demonstrate that it became drier during the Middle Holocene. This period roughly coincides with the Middle Archaic Period. Forests became more open and dominated by oak and hickory, and prairie expanded in the Illinois area. The opening of the forest would have benefitted animals, such as white-tailed deer, that browse on brushy vegetation. The expansion of prairie would have benefited grassland animals.

The warm and dry climate of the Middle Holocene led to the expansion of prairie (dark brown on map) and the opening of the forest in the Illinois area. The Grand Prairie that historically covered Central Illinois owes its origin to this period. Edgar Transeau named this prairie extension the Prairie Peninsula. It extended from the western grasslands across Illinois and further east. He published this map in the journal Ecology in 1935.

During this time, prairies expanded in the central part of Illinois. At Modoc, we recovered remains from a few prairie species such as Greater Prairie Chicken, badger (Taxidea taxus), spotted skunk, and Plains pocket gopher. The prairie taxa are present in the middle and late part of the Middle Archaic at Modoc. Changes in the species of terrestrial snails present in the deposits at Modoc (see image of snails below) indicate that it became warmer and dryer at this time. Terrestrial snails may have been naturally attracted to the garbage in the pits. Some of the larger terrestrial snails may have been collected and eaten. Regardless of how the snails arrived at the site, they provide good indications of environmental conditions. During the Middle Archaic Period, prairie expanded in Illinois creating a peninsula of prairie extending from the great prairies to the west far to the east (see map above).

Percentages of white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) bone increased in the Middle Archaic deposits at Koster and in the Main Shelter at Modoc, and percentages of tree squirrel bones declined. Deer prefer open forest and forest edge, and would have benefited from the increased browse with the opening of the forests during the Middle Archaic. The numbers of deer may have increased.

We created a Resource Type Ontology in tDAR. It allowed us to categorize all of the remains from our sites based on taxa of known importance and gross resource types. The full ontology includes 26 types (see table below). We used the tDAR integration tool to generate a new Excel database to summarize and compare the abundance of resource types for each of the cultural subperiods for the Modoc Main and West Shelters and the Koster site.

| Resource Type Ontology | Description |

|---|---|

| Bison | Bison bison |

| Deer | Odocoileus spp. (white-tailed or mule deer) |

| Other Ungulates | Elk, moose, or indeterminate deer or elk (Cervidae) |

| Other Large Mammals | Any other deer-sized or larger mammal |

| Semi-aquatic Mammals | Animals that live on the land and in the water, such as beaver, muskrat, and river otter |

| Other Medium Mammals | Any other mammal larger than a tree squirrel and smaller than a deer |

| Tree Squirrels | Squirrels that climb and live in trees, i.e. gray squirrel, fox squirrel, red squirrel, Southern flying squirrel |

| Rabbits | Sylvilagus spp., eastern cottontail or swamp rabbit |

| Other Small Mammals | Any other small mammal of tree squirrel size or smaller |

| Indeterminate Mammals | Mammal remains that are not placed in any of the above categories |

| Aquatic Birds | Any birds associated with aquatic habitats |

| Other-Non-aquatic Birds | Any birds associated with terrestrial habitats |

| Indeterminate Birds | Birds that are not identified as either aquatic or terrestrial, indeterminate birds |

| Aquatic Turtles | Turtles associated with aquatic habitats |

| Terrestrial Turtles | Turtles associated with terrestrial habitats |

| Indeterminate Turtles | Turtles that cannot be identified as either aquatic or terrestrial, indeterminate turtle |

| Other Reptiles | All non-turtle reptiles, such as snakes, lizards, indeterminate reptiles |

| Amphibians | All amphibians |

| Fish | All fish |

| Indeterminate Vertebrate | Vertebrates not identified to one class of animals, e.g., indeterminate vertebrate, bird or mammal, herptile |

| Bivalves | Aquatic mollusks with a hinged shell with two halves, e.g., freshwater mussels, clams |

| Aquatic Grastropods | Univalve mollusks (snails) associated with aquatic habitats |

| Terrestrial Gastropods | Univalve mollusks (snails) associated with terrestrial habitats |

| Indeterminate Gastropods | Univalve mollusks (snails) that cannot be identified as aquatic or terrestrial snails, indeterminate gastropods |

| Invertebrates | Indeterminate invertebrates, such as mollusk shells that cannot be identified as bivalves or snails, insects, crayfish. |

| Unknown | Unknown animal |

The tDAR integration of our datasets using the Resource Type Ontology allows us to detect broad patterns. For example, the early Early Archaic deposits at the West and Main shelters at Modoc Rock Shelter show the highest percentages of bones that could only be classified as indeterminate vertebrates and indeterminate birds when compared to the other cultural subperiods. This finding indicates that a smaller proportion of the bones could be identified to levels that would tell us something about the environment. Use of all the categories does allow us to grossly divide faunal remains into those from animals associated with aquatic and terrestrial habitats. However, the broader categories are not useful for more detailed interpretations of past environments.

Because it is difficult to compare sites using so many categories, we also ran an integration to compare abundances of key resource types that we knew were important across at least parts of our study area. These key resource types would allow us to look at changes in use of important aquatic and terrestrial resources that might relate to environmental changes. The key resource types include three terrestrial resources (deer, tree squirrel, and rabbit) and five resources associated with aquatic habitats (semi-aquatic mammals, aquatic birds, aquatic turtles, fish, and bivalves).

Aquatic Environments

Geological studies of landforms and sediments show that river systems changed dramatically during the Archaic Period at the Ice Age to Holocene transition. Archaeologists and geologists have long noted that Holocene stabilization of sea level, the Great Lakes, and river systems led to increased productivity of aquatic resources. During cold periods within the Ice Age, water was tied up in glaciers and the sea level was substantially lower. The Great Lakes as we know them were covered with Glacial Ice. During warm periods when glaciers were melting or when glacial lakes breached their dams, rivers and floodplains were ravaged by great torrents of glacial meltwater. These great floods were not beneficial to aquatic animals or to humans living in floodplains.

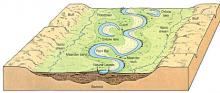

The development of natural levees along the Illinois River helped maintain the river in a single channel and was also important to the establishment of the shallow floodbasin lakes. Diagram in the Public Domain.

During the Holocene, the major rivers in Illinois began to stabilize. Geologist Edwin Hajic provided the following reconstruction for the lower Illinois River valley. During the late Ice Age, the Illinois River flowed through multiple channels in the floodplain. During the Early Holocene, sediments deposited by the Mississippi River dammed the mouth of the Illinois River and caused a large lake to form in the lower Illinois River valley. This lake filled the lower Illinois valley during much of the Early and Middle Holocene. The Illinois River flowed into this large lake. Through time, the river deposited resistant natural levees along its channel. Deep lakes formed between the floodplain side of the levees and sediments deposited by secondary streams.

When the Illinois River floods, it fills shallow depressions in the floodplain with water. The top image shows the lower Illinois River valley north of Silver Creek during a spring flood. The floodwaters cover most of the floodplain. The large clump of trees in the image covers a 2,000 year old American Indian mound (Kamp Mound). The bottom image shows a floodbasin lake north of Silver Creek that was refilled by floodwaters during the spring flood. These shallow floodplain lakes were established by 5,700 RCYB during the late Middle Archaic Period. Images taken by Bonnie Styles.

During the late Middle Holocene, sediment deposited by the secondary streams and the river began to infill these lakes. By the late Middle Archaic, the Illinois River had become a relatively straight, low gradient river flowing in a single channel bounded by natural levees with shallow lakes in the floodplain. The geological evidence suggests that shallow floodplain lakes emerged around 5,700 RCYBP. This floodplain configuration continued into the Late Archaic and historic times.

At the Koster site, increased proportions of species that live and feed in shallow, quiet water provide faunal evidence for the development of the floodbasin lakes during the late Middle Archaic. These quiet-water species include freshwater mussels, especially the giant floater (Pygandon grandis corpulenta) (top image, taken by Robert Warren), quietwater fish such as the brown bullhead (Ameiurus nebulosus) (middle image, taken from Wikimedia Commons), and dabbling ducks, including the Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos) (bottom image, taken from Wikimedia Commons).

The increased proportions of thin-shelled freshwater mussels that prefer quiet water, dabbling ducks that feed in shallow water, and quiet-water fish at the Koster site suggest the presence and use of shallow lakes in the Illinois River floodplain by 5,700 RCYBP during the late part of the Middle Archaic Period. The proportion of fish remains in the deposits dramatically increased at this time. The increased use of fish may be linked to the great productivity of these floodbasin lakes. We will discuss this issue in the section on Human Use of Animals.

During Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene, the Mississippi River showed a braided stream pattern. The river flowed in multiple paths down the channel. The diagram of a braided stream was taken from Endreny, T.A., 2003, Fluvial Geomorphology Module, UCAR COMET Program and NOAA River Forecast Center.

The Mississippi River System differs from the Illinois River System today, and it did in the past as well. The Mississippi River has a higher gradient, a heavier bed load, and is not straight. Based on geological research by Dr. Edwin Hajic and others, the Mississippi River system evolved from a braided stream with multiple flow paths in a single channel to a meandering system. Oxbow lakes formed in abandoned channel segments of the meandering river system around 8,000 RCYBP.

By the late Early Archaic to early Middle Archaic Period, the Mississippi River had evolved into a meandering river system with oxbow lakes in abandoned channels. Diagram of a meandering river taken from the University of Indiana.

The timing for the emergence of shallow oxbow lakes occurred earlier than the appearance of shallow floodbasin lakes in the Illinois River valley. The oxbows may have been present around 8,000 RCYBP in the Mississippi River valley.

Shells from terrestrial gastropods (snails) (left side of image) and aquatic gastropods (right side of image) made up about 12% of the total faunal remains in some Archaic camp deposits in the West Shelter at Modoc Rock Shelter. In 1956, archaeologists recovered the shells in this image from a single test unit level in early Middle Archaic deposits. The snails date to about 8,000 RCYBP. Image taken by Bonnie Styles.

The faunal remains from Modoc Rock Shelter support the geological data. There were relatively few fish and bivalve remains in the two Early Archaic deposits in the West Shelter at Modoc (see bar graphs above). The Main Shelter at Modoc showed a higher proportion of fish than did the West Shelter in the late Early Archaic.

The proportion of fish increased in the early Middle Archaic around 8,000 RCYB in the Main Shelter but is relatively high throughout the Archaic Period. The proportion of bivalves in the Main Shelter increased slightly in the middle Middle Archaic and remained about the same in the late Middle Archaic. Most of the mussel taxa in the Modoc deposits are large river forms so this increase could relate to stabilization of river systems. The proportion of fish and bivalves in the West Shelter at Modoc also increased in the early Middle Archaic around 8,000 RCYBP and remained high through the middle Middle Archaic.

The West Shelter showed relatively high proportions of aquatic gastropods from the late Early Archaic through the middle Middle Archaic. It was not possible to determine the proportion of the fauna attributed to gastropods for the Main Shelter because the snails were analyzed differently. However, Dr. James Theler, an expert on gastropod identification, reported that use of aquatic gastropods in the Main Shelter was much less than in the West Shelter.

Mussels and aquatic gastropods do best in streams and rivers with current to circulate their food and stable bottoms that allow them to stay in place. The Mississippi River had stabilized sufficiently by the late Early Archaic to support the development of freshwater mussel and aquatic gastropod beds.

Slight increases in thin-shelled mussel species and fish species associated with quiet water habitat in the early part of the Middle Archaic Period at Modoc support the geological evidence for the early presence of oxbow lakes in this area.

The species composition of the mussel assemblage provides information on the characteristics of the water habitats near the site. Thin-shelled mussels, such as this well-preserved shell from a pond horn (Uniomerus tetralasmus) (top image, taken by Doug Carr) from the middle Middle Archaic deposits at Modoc Rock Shelter provides evidence for relatively shallow, standing water near the site. Thick-shelled mussels such as this large river form of a threeridge (Amblema plicata plicata) (bottom image, taken by Bonnie Styles) from the early Middle Archaic at Modoc, provide evidence for large river habitat with swift to moderate current.

Analyses of the kinds of species present for freshwater mussels from the Koster and Modoc sites provided important information on the changes in aquatic habitats in the Illinois and Mississippi River valleys during the Archaic Period. Using the UNIO program developed Dr. Robert Warren, we analyzed the percentages of mussel species associated with different water body types (from large river to lake), current speed (from swift to standing), water depth, and bottom type (from cobbles and gravel to mud) to get a sense of changes in aquatic habitats.

At the Koster site, the use of freshwater mussels increased around 7,500 RCYBP during the middle part of the Middle Archaic Period. Most of the species are associated with large rivers with current. Because mussels rely on moving water to circulate their food, rivers with current usually provide better habitat than lakes with quiet water. At this time, relatively few species are associated with lake habitats and standing water. This initial increase in freshwater mussels suggests that the river had stabilized sufficiently to support the establishment of mussel beds.

At Koster, the percentage of mussels associated with lakes and standing water increased dramatically in the late Middle Archaic Period. At this time the number of mussels associated with lakes is about equal to that for large river. This is largely because thin-shelled floaters (the giant floater, Pyganodon grandis corpulenta, and the flat floater, Anodonta suborbiculata) dominate the assemblage and are scored equally in UNIO for large rivers and lakes because they live in quiet waters of both habitats. Most of the mussels in the late Middle Archaic camps are associated with standing or slow water. Before and after that time, more mussels at the Koster site are associated with river habitat with swift to moderate current. Several zooarchaeologists link the increase in thin-shelled mussels to the emergence of the shallow lakes. However, remember that mussel populations actually do better in rivers with current to circulate their food so it is unlikely that procurement in the river would cease after the emergence of the shallow lakes.

Throughout the Archaic Period at Modoc Rock Shelter, most of the mussels in the Main Shelter are associated with larger river habitat with swift to moderate current. The percentage of mussels associated with lake habitat at Modoc is greatest in the early and middle parts of the Middle Archaic, and is low in the late Middle Archaic. The percentage of mussels associated with lake habitat is much lower for Modoc than was noted for Koster. However, these analyses and the early presence of some quiet-water species support the geological evidence that shallow lakes were present earlier in the Mississippi River valley (near Modoc) than in the Illinois River valley (near Koster).

During the Holocene, river systems became more stable, which was beneficial for a wide variety of species, including fish, aquatic turtles, freshwater mussels and gastropods, amphibians, waterfowl, and semi-aquatic mammals such as muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus). The stable rivers in the Illinois and Mississippi River floodplains offered richer aquatic resources to Early Archaic Period people than were available to the Paleoindians of the Late Ice Age. With the evolution of the shallow floodplain lakes, the productivity of aquatic habitats increased even more for the Middle Archaic occupants. During the Middle Archaic Period, people in the Illinois area concentrated their villages along the edges of the major river valleys and were taking greater advantage of the rich aquatic resources in the floodplains.

The faunal data from the Archaic sites in our study area provided important information on changes in the forest and rivers during the Archaic Period. Changes in forests and river systems were important for all the regions in the study area for our grant. Changes in water level in the Great Lakes also played a role in river stabilization across the study area. They also were important to aquatic resource availability for our Michigan sites. Environmental changes at least stimulated changes in human use of aquatic resources. We will explore this topic more in the section on Human Use of Animals.

Threeridge mussels (Amblema plicata) from the middle Middle Archaic (Horizon VIII) deposits at the Koster site (left side of image) show a more elongate morphology. The same species from the late Middle Archaic (Horizon VI) deposits at the Koster site (right side of image) has a more rounded shape. The raised beaks at the bottom of the shells in the image indicate these are both large river forms that likely came from the Illinois River. These morphological differences suggest a change in the flow of the river. Image taken by Bonnie Styles.

Changes in Animal Morphology and Clinal Variation in Body Size

As noted before, morphological changes in a species may indicate environmental change. For example, zoologist Frederick C. Hill recorded a morphological difference in the shells of the threeridge (Amblema plicata) mussel between two Archaic Period levels at the Koster site. He compared measurements of length and height for threeridge shells from middle Middle Archaic Period (Horizon VIII) and late Middle Archaic (Horizon VI) at the Koster site. The threeridge shells were more elongate in the older layer (Horizon VIII) and more oval in the younger layer (Horizon VI) layer.

He attributed the difference in shell morphology to changes in flow for the Illinois River during the two time periods. Although it is possible that the freshwater mussels were collected from different rivers, the most likely source in both cases was the Illinois River. The threeridges from both time periods show the raised beaks (umbones) characteristic of large river forms.

Gray squirrels (Sciurus carolinensis) (top image), fox squirrels (Sciurus niger) (center image), and eastern cottontails (Sylvilagus floridanus) (bottom image) showed clinal variation in body sizes during the Archaic Period at sites in Missouri. This variation is related to environmental changes in their habitats. Images taken from Wikimedia Commons.

As noted before, Dr. James R. Purdue demonstrated that there were changes in the body sizes of gray squirrels, fox squirrels, and eastern cottontails during the Archaic Period in Missouri. These species currently show variation in body size from East to West, with the species having the largest body size in the region with the habitat best suited to them. This type of variation is called clinal variation. Dr. Purdue argued that the changes he saw through time reflected changes in the quality of habitat. He argued that environmental change was responsible for the changes in habitats and body size. Thus, differences in the size and shapes of animals can indicate changes in the environment. Although we did not do these kinds of analyses for our grant, we think they would yield interesting results.

The astragalus from late Middle Archaic deposits at the Koster site (left side of image) is smaller than those from the modern adult female deer (center of image), and the modern adult male deer (right side of image) from the comparative collection. Image taken by Bonnie Styles.

Dr. Purdue also documented differences in the body size of white-tailed deer. He analyzed measurements of astragali (a tarsal bone in the lower back leg). He noted that deer from Middle Holocene deposits at Modoc Rock Shelter and Koster were smaller than deer from later prehistoric sites (Woodland and Mississippian Periods). He attributed the small body size of Middle Archaic deer to Middle Holocene climate change. Warming and drying of the climate had negative effects on the quality of forage during the critical summer period of growth for deer.

References

Past Environments

*non-technical

Baker, Richard G., L. A. Gonzalez, M. Raymo, E. A. Bettis III, M K. Reagan, and J. A. Dorale. 1998. Comparison of Multiple Proxy Records of Holocene Environments in the Midwestern United States. Geology 26:1131-1134.

Baker, Richard G., Louis J. Maher, Craig A. Chumbly, and Kent L. Van Zant. 1992. Patterns of Holocene Environmental Change in the Midwestern United States. Quaternary Research 37:379-389.

Brown, Paul, James P. Kennett, and B. Lynn Ingram. 1999. Marine Evidence for Episodic Floods Holocene Megafloods in North American and the Northern Gulf of Mexico. Paleooceanography 14:498-510.

Grimm, Eric and George L. Jacobson Jr. 2004. Late-Quaternary Vegetation History of the Eastern United States. Pp. 381-482 In The Quaternary Period in the United States, edited by A. R. Gillespie, S. C. Porter, and B. F. Atwater. Elsevier, Amsterdam.

Hajic, Edwin R. 1990. Late Pleistocene and Holocene Landscape Evolution, Depositional Subsystems, and Stratigraphy in the Lower Illinois River Valley and Adjacent Central Mississippi River Valley. Ph.D. dissertation. University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign.

Hill, Frederick C. 1975. Effects of the Environment on Animal Exploitation by Archaic Inhabitants of the Koster Site, Illinois. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Louisville.

Kapp, Ronald O. 1999. Michigan Late Pleistocene, Holocene, and Presettlement Vegetation and Climate. Pp. 31-58 in Retrieving Michigan’s Buried Past: The Archaeology of the Great Lakes State, edited by J. R. Halsey. Cranbrook Institute of Science, Bloomfield Hills, MI.

Klippel, Walter E. and James Maddox. 1977. The Early Archaic of Willow Branch. Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology 2(1):99-130.

Larsen, Curtis E. 1999. A Century of Great Lakes Research: Finished or Just Beginning? Pp. 1-30 in Retrieving Michigan’s Buried Past: The Archaeology of the Great Lakes State, edited by J. R. Halsey. Cranbrook Institute of Science, Bloomfield Hills, MI.

Lovis, William A. 1986. Environmental Periodicity, Buffering, and the Archaic Adaptations of the Saginaw Valley of Michigan. Pp. 99-160 in Foraging, Collecting, and Harvesting: Archaic Period Subsistence and Settlement in the Eastern Woodlands, edited by S. Neusius. Center for Archaeological Investigations, Occasional Papers 6. Southern Illinois University, Carbondale.

Lovis, William A. 2009. Hunter-Gatherer Adaptations and Alternative Perspectives on the Michigan Archaic: Research Problems in Context. Pp. 725-754 in Archaic Societies: Diversity and Complexity across the Midcontinent, edited by T. E. Emerson, D. L. McElrath, and A. C. Fortier. State University of New York Press, Albany.

McMillan, R. Bruce. 1976. The Dynamics of Cultural and Environmental Change at Rodgers Shelter in Missouri. Pp. 211-232 in Prehistoric Man and His Environments: A Case Study in the Ozark Highland, edited by W. R. Wood and R. B. McMillan. Academic Press, New York.

McMillan, R. Bruce. 2006. Perspectives on the Biogeography and Archaeology of Bison in Illinois. Pp. 67-147 In Records of Early Bison in Illinois, edited by R. B. McMillan, Illinois State Museum Scientific Papers 31. Illinois State Museum, Springfield.

McMillan, R. Bruce. 2014. Holocene Range Expansion of Pronghorn into the southern Prairie Peninsula. Pp. 269-283 in Archaeology, Zooarchaeology, and Malacology: A Festschrift for James L. Theler, edited by M. G. Hill. The Wisconsin Archeologist 95(2).

McMillan, R. Bruce and Walter E. Klippel. 1981. Post-Glacial Environmental Change and Hunting and Gathering Societies of the Southern Prairie Peninsula. Journal of Archaeological Science 8:215-245.

Montgomery, David and Ellen E. Wohl. 2004. Rivers and Riverine Environments. Pp. 221-246 in The Quaternary Period of the United States. Elsevier, Amsterdam.

Morey, Darcy F. and George M. Crothers. 1998. Clearing Up Clouded Waters: Paleoenvironmental Analysis of Freshwater Mussel Assemblages from the Green River Shell Middens, Western Kentucky. Journal of Archaeological Science 25: 907-926.

Nelson, David M., Feng Sheng Hu, Eric C. Grimm, B. Brandon Curry, and Jennifer E. Slate. 2006. The Influence of Aridity and Fire on Holocene Prairie Communities in the Eastern Prairie Peninsula. Ecology 87:2523-2536.

Parmalee, Paul W., R. Bruce McMillan, and Frances B. King. 1976. Changing Subsistence Patterns at Rodgers Shelter. Pp. 141-162 in Prehistoric Man and His Environments: A Case Study in the Ozark Highland, edited by W. R. Wood and R. B. McMillan. Academic Press, New York.

Purdue, James R. 1980. Clinal Variation of Some Mammals during the Holocene of Missouri. Quaternary Research 13:242-258.

Purdue, James R. 1986. The Size of White-tailed Deer (Odocoileus virginianus) during the Archaic Period in Central Illinois. Pp. 65-95 in Foraging, Collecting, and Harvesting: Archaic Period Subsistence and Settlement in the Eastern Woodlands, edited by S. Neusius. Center for Archaeological Investigations, Occasional Papers 6. Southern Illinois University, Carbondale.

Purdue, James R. 1989. Changes during the Holocene in the Size of White-tailed Deer (Odocoileus virginianus) from Central Illinois. Quaternary Research 32:307-316.

Purdue, James R. 1991. Dynamism in the Body Size of White-tailed Deer (Odocoileus virginianus) from Southern Illinois. Pp. 277-283 in Beamers, Bobwhites, and Blue-Points: Tributes to the Career of Paul W. Parmalee, edited by J. R. Purdue, W. E. Klippel, and B. W. Styles. Illinois State Museum Scientific Papers 23.

Purdue, James R. and Bonnie W. Styles. 1987. Changes in the Mammalian Fauna of Illinois and Missouri during the Late Pleistocene and Holocene. Pp. 144-174 in Late Quaternary Mammalian Biogeography and Environments of the Great Plains and Prairies, edited by R. W. Graham, H. A. Semken, Jr. and M. A. Graham. Illinois State Museum Scientific Papers 22.

Styles, Bonnie W. 1986. Aquatic Exploitation in the Lower Illinois River Valley: the Role of Paleoecological Change. Pp. 145-174 In Foraging, Collecting, and Harvesting: Archaic Period Subsistence and Settlement in the Eastern Woodlands, edited by S. Neusius. Center for Archaeological Investigations, Occasional Papers 6. Southern Illinois University, Carbondale.

Styles, Bonnie W. 2006. Northeast Animals. Pp. 412-427 in Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 3. Environment, Origins, and Populations, edited by D. E. Ubelaker. Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C.

Warren, Robert E. 1992. UNIO: A Spreadsheet Program for Reconstructing Aquatic Environments Based on the Species Composition of Fresh-Water Mussel (Unionidae) Assemblages. Illinois State Museum Quaternary Studies Program, Technical Report 92-000-3.

Wood, Raymond W. and R. Bruce McMillan (editors). 1976. Prehistoric Man and His Environment: A Case Study in the Ozark Highland. Academic Press, New York.